Life In The 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron

Osan AB (K55), Korea – 1956-57 ~ Part 1In 1956-57, I was stationed at Osan AFB (K55), Korea, in the 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing, 5th Air Force. During that time, I was an enlisted man working in the Radar/Fire Control Section. 1/Lt Robert Ford was one of our pilots; but, as in normal military protocol and life, although I knew him, he did not know me. At least, as far as I know, Lt. Ford did not know me.

However, I had great respect for him as a person, as well as an officer. Bob Ford was from Mississippi and Alabama; standing almost 6’5″, he was very noticeable among the other pilots who typically stood about 5’8″ to 6’0″ tall. And, of course, for all young Jesse James fans, the name Bob Ford is infamous. But, the one thing that made Bob Ford stay in my memory for almost fifty years was his respect for others. He was the only pilot I ever met who would refuel his own plane, rather than call the crew chief back from the barracks, when his flight landed after hours.

So, although Bob Ford has stayed in my memory all these years, I cannot say that we were friends, just that I admired him. Because of this, my memories I will write below, rather than give the reader personal incidences of Bob Ford’s life in Korea – I want to paint a picture for you of what life was like in the 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, at Osan (K55), Korea, at that time. Even though this picture will be seen through the eyes of an enlisted man, life was not all that much better for the officers/pilots. The picture I paint will be done in both words and in photographs – that you may get a more complete taste of life at K55 in 1956-57.

HI HO, HI HO, IT’S OFF TO SERVE WE GO!

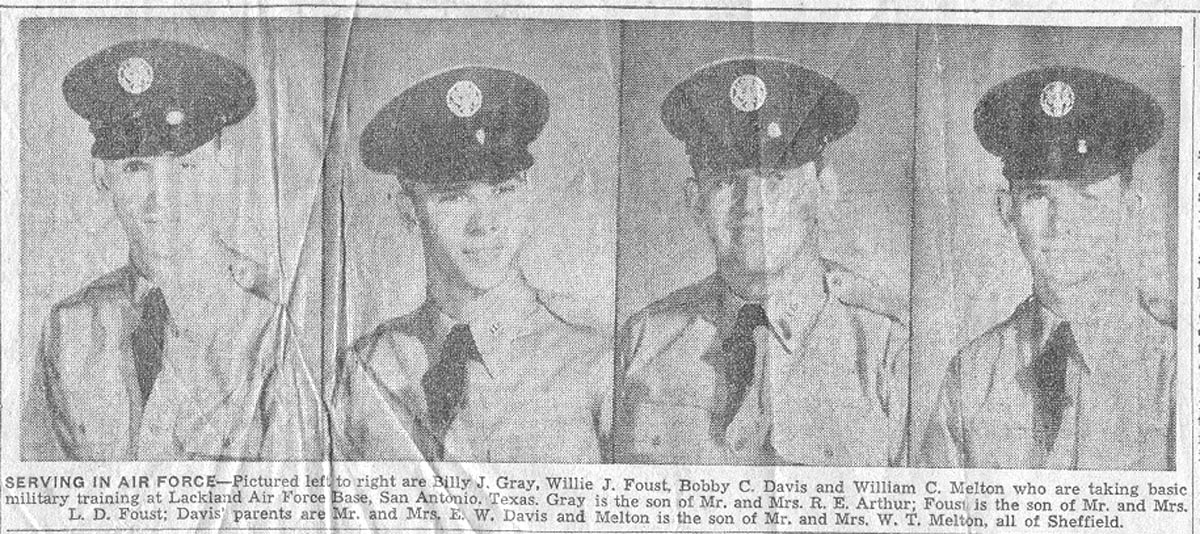

At the age of 17, one week out of Sheffield High School in Sheffield, Alabama, three friends – Bob Davis, Willie Joe Foust, Cortez Melton – and I joined the Air Force and were off to the USAF Induction Center at Montgomery, Alabama. After being sworn in as a group of sixty kids from Alabama and Florida, what the Air Force calls a Flight, we were put on a train headed to Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas, for eleven weeks of Basic Training. Mind you, we joined in June 1955, which meant that we spent June, July, and August in Texas – with our one week of bivouac, living in the field in tents and doing all the obstacle courses, mud crawling, and other such fun things — in the hot Texas August sun.

After Basic Training we were all sent to separate Technical Schools for career field training. Luckily, I received electronic training in Radar/Fire Control School at Lowry AFB in Denver, Colorado. Fire Control meaning aircraft weapons radar target tracking and sighting system; not fighting forest fires. My training was on the sleek F-86F jet fighter; a plane, that, to this day, I still consider one of the most beautiful fighter aircraft ever built.

I arrived at Lowry AFB in Denver, Colorado, in October 1955, for six months of Technical School training and in the first part of April 1956, I was given orders shipping me to Osan AFB (K55), Korea. I rode a Greyhound bus from Denver to a MATS (Military Air Transport Service) base somewhere near Oakland, California. In the Spring of 1956 I saw the green rolling hills of Northern California for the first time and fell in love with them.

From California I flew on a Lockheed Constellation, the long sleek passenger airliner with the triple-tail configuration -â three vertical sections set in a horizontal stabilizer — and propellers instead of jet engines. We flew about 16 hours to Midway Island, refueled, and then on to Osan AFB, Korea.

My first night at Osan AFB, I stayed in a transient barracks near the ROK (Republic of Korea) Army barracks. Unfortunately, no one warned me about the midnight visitors. About midnight, I woke to see a shadowy figure grabbing my travel bag (ditty bag), several other bags, and running out of the barracks. The Air Police came with their K9 unit, a big ferocious German Shepherd which kept straining so hard to follow the thief I thought his chain would break. We all were able to follow the footsteps right to the fence separating us from the ROK barracks, leaving no doubt where the thief lived.

The next day, I was assigned to the Radar/Fire Control ection of the 311th Fighter Bomber Squadron. We had 24 F-86F aircraft in our squadron, divided into three flights of eight aircraft. Aircraft would typically go up in a flight of four for target practice or simulated bomb runs. When they returned, several of us would jump on our Radar/Fire Control jeep and go meet each pilot as they taxied into the revetment, to see if there were any problems with the radar/fire control sighting system.

One thing I learned quickly – the Air Force practices segregation. All the radar and communications guys lived in the same quonset huts. And all the A&E (airframe and engine) mechanics lived in other quonset huts. The squadron had about three times as many A&E mechanics compared to the radar and communications technicians. And, those who ran the squadron, i.e., the First Sergeant and all who worked in the Squadron Orderly Room, were mostly A&E types. To them the radar and communications types were “those whiz kids” – my first experience in being the despised minority.

Besides the officer who was the OIC (officer in charge) of our Radar shop, our exposure to the pilots was usually limited to those brief moments when they returned from a flight. However, we soon got to know who were the “good guys” and who were the “not so nice guys.” I learned quickly that 1/Lt. Bob Ford stood out from the rest. We were often told by the A&E mechanics, the guys who were responsible for making sure the aircraft was refueled, loaded with armament, and ready for business – that often when Lt. Bob Ford landed later in the evening after most enlisted men had gone back to our barracks; rather than send for a mechanic to refuel his plane, Bob Ford would do it himself. This was not typical of pilots.

CREW CHIEF REFUELING AN F-86F AIRCRAFT

Another reason he stood out was his name – Bob Ford. Anyone who grew up being a Jesse James fan knows who Bob Ford was; that dirty, sneaking coward who shot Jesse in the back. Of course, except for the name, there was no other resemblance between the two Bob Fords.

And, as icing on the cake, Bob Ford was a Southern boy like me. He grew up in Mississippi and later lived in Huntsville, Alabama. If he had been about six years younger, I might have played against him in high school basketball since my school did sometimes compete against Huntsville.

Another thing I learned upon arriving in Korea – I was not going to be living in a nice, comfortable, American style barracks as I had up until now. In Korea, we lived in 20-man quonset huts. Our bathroom and showers were in another quonset hut across the street.

The photo on the left below is our 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron street of living quarters – the building on the right side in that photo below is our latrine, i.e., shower, toilet, and all other personal hygiene functions. The photo on the right is me sitting in front of my lovely Korean home.

Let me explain more about what the Air Force considered a toilet at Osan AFB. Forget fancy stalls with doors for privacy. Picture a wooden box, about thirty feet long, with a hole cut out about every three foot, and a stream of water running underneath the length of box – that was our toilet. There was always the joke about a guy taking a wad of toilet paper, setting it afire, and letting it float down the stream. About ten guys could sit down, chat, close enough to hold hands if so desired, and do their business. Of course, if a wad of burning paper were set loose, you would have seen guys popping up and down like fans at a football game doing the “wave.”

The only building on the base that had a normal toilet – you know, nice white ceramic bowls, stalls with doors that closed, etc. – was the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing Headquarters building. Being a pragmatic, and whenever possible, a private person; I found it practical to train myself to make my toilet visits after I left work in the afternoon, when I could walk to the HQ building and relax. I cannot say for certain, but I would imagine the pilots, gentlemen or not by act of Congress, were pretty much in the same boat as we enlisted men. As far as I know, only the General and Staff Officers had such white ceramic luxuries.

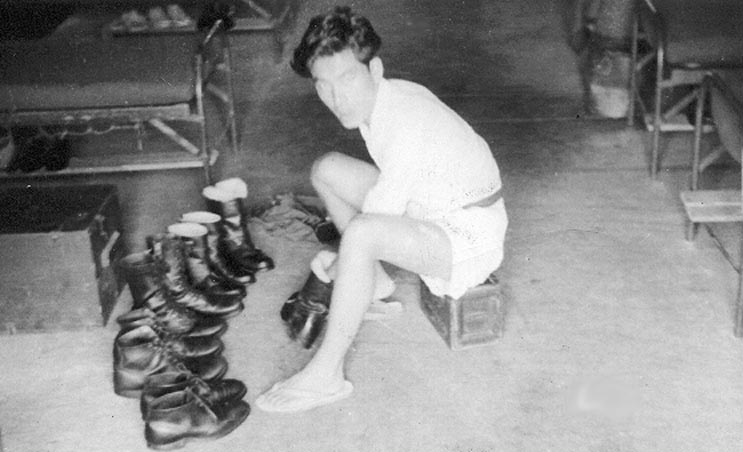

The photo above left shows you the beautiful landscaping at the front entrance way to our villas in Osan, Korea; with rolling brown hills behind. Truly living in the lap of luxury. To complete this picture of luxury, the photo above right is Mike, the Korean houseboy for my quonset hut. Each quonset hut had their own houseboy. I believe that each of us paid Mike about $1.50 to $2.00 a month. For that he kept our hut clean and kept our boots and shoes shining. Not a bad deal, even in 1956.

Mike was a very nice guy, easy to get along with, very pleasant – except for his kimchi breath. I am not kidding; when Mike walked into the quonset hut, from the other end, you could smell the kimchi on his breath – from forty to fifty feet away.

For those of you not familiar with this Korean delicacy, kimchi; it is a dish made from cabbage, flavored with garlic, red pepper, ginger, salt, and other spices. Then, traditionally, kimchi is put into ceramic crocks and buried in the earth until it ferments. I have never eaten kimchi; but, if you are within fifty foot of someone who has, you will know it.

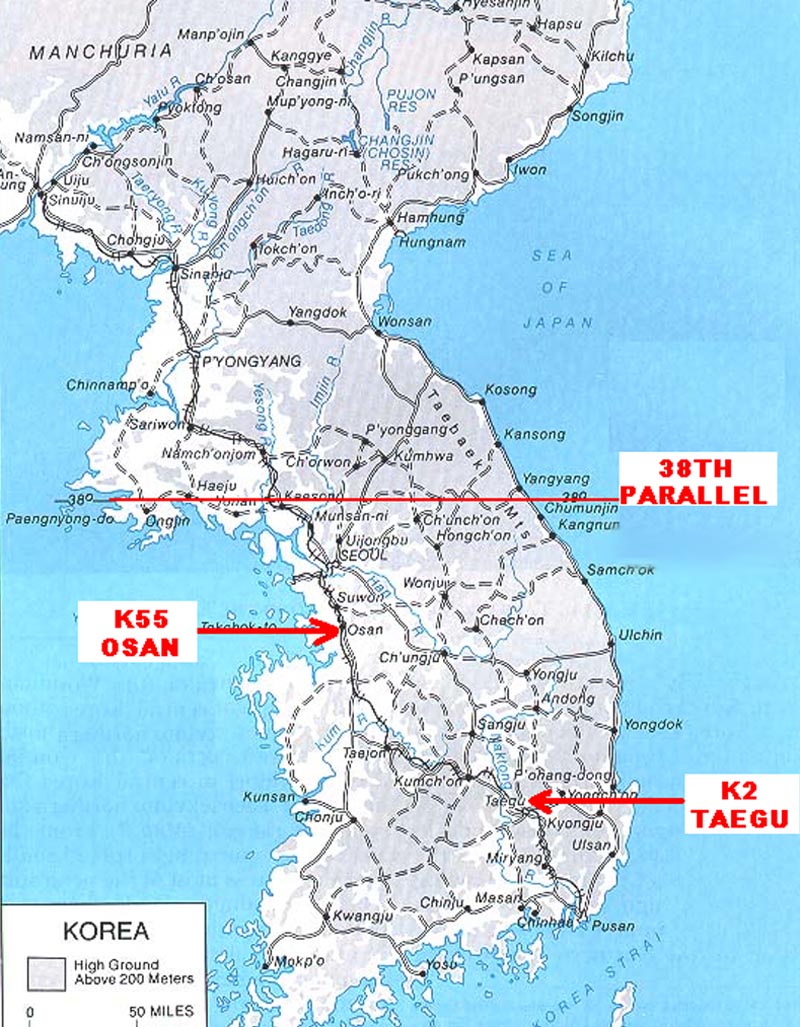

The 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron was one of three squadrons in the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing, 5th Air Force, which called Osan AFB (K55) home. The other two squadrons were the 310th and the 69th. The 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing was stationed at K2, Taegu, during the Korean War. In 1955, the wing was moved to K55 at Osan. Notice in the photo below that Red China (Manchuria) is at the top left of the map, across the Yalu River. The Communist Chinese had only to cross the Yalu River to join their comrades, the North Koreans, to supply them with weapons and to eventually join them in the fighting. Support for North Korea was just across the river; support for South Korea and the American and Allied troops came from our bases in Japan.

The 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron sign below sat at the entrance to our work and flight line area. The sign was about 5 foot wide and 3 foot high. Quite honestly, I always felt a surge of pride as I walked past this sign going to work in the Radar/Fire Control Systems shop. In our shop, a corrugated tin room about 12 foot square, we had three to four technicians who worked on the test benches repairing the radar sets and sighting system analog computers. About a dozen of us worked on the aircraft sitting on the flight line, testing and replacing radar and computer modules. The only names I can remember of those working in the shop are a quite A/1C named Ken; a muscle builder named Johnson, who spent all his free time sparring with a punching bag; and a very nice African-American A/1C (back then we just said Black) named Shuler.

In the flight line crew, I recall Mark Churchill from Lubbock, Texas, my good friend and a fantastic artist who could take a simple pencil and white pad and make the most beautiful shades of gray drawings; Bob Jones, who was an oil field roustabout in Oklahoma before joining the Air Force; Jose “Joe” Valdez, my amigo; and a young guy from Boston named Francis who always got mad at me for making fun of his name – yet, when a cocky A/1C in our radar shop threatened to report me for hitting him, Francis stood up for me. Friends always do in time of need. Then, there was my good friend, James “Smitty” Smith, an African-American from Arkansas. There are many other faces I can see in my mind, but cannot yet put names to them.Probably one of my closest friends in Korea was an African-American named Bob White. It always struck me funny – I am a Caucasian named Gray; and he was a Black man named White. One of life’s little idiosyncrasies. Bob was an extremely talented guitarist who taught me to appreciate and love all forms of jazz music. He formed a jazz trio and played on the base radio station. Often, I would go with him and the trio to the back room of the Enlisted Men’s Service Club where they would practice. Talk about a taste of heaven – this very talented jazz trio, three black musicians, jamming – and their audience of one tall, skinny, white guy sitting there for hours, loving it. Bob seldom went out partying and drinking; he stayed on the base and played his guitar. That was his total pleasure.

Although, Bob did tell me about one of his other friends, an enlisted man in the Medics who would occasionally load a bunch of his friends into an ambulance, turn on the red flashing lights, and go flying through the base gate as though there was an emergency outside the base. After a few hours of partying, they would load up again in the ambulance, turn on the red flashing lights, and rush back through the gates to the base. As far as I know, the Air Police at the gate never caught on to their trick. I believe that Bob made at least one of these excursions with his friend.

Bob was a radio communications technician who had trained to work on the B47 bomber; but ended up being sent to Korea where there was not one B47. So, he worked on F-86F radio communications.

At the end of our one year tour of duty in Korea, as we were getting ready to ship back to Bergstrom AFB in Austin, Texas; Bob came to me and said, “You know that when we get back to the States, we cannot run around together.” I was shocked. Here I was, a white boy raised in Alabama (but, praise the Lord, not in a home where prejudice was taught) – and I had not even thought about that. But, I realized that what he told me was right. In Texas, in the late 1950s, he could not go to the clubs with me; and I could not go to his clubs with him. A thought that makes me sad, even to this day.

At Bergstrom AFB, Bob and I were in different squadrons and I lost track of Bob. Over the years I have often thought of him; but had no idea how to get in touch. Several years ago, I saw a Chicago Jazz informercial on television – and there was Bob. It was an old video, but it was Bob; no doubt about it. On a hunch, I sent an e-mail to MoTown Records, and had a response in about thirty minutes. Bob had been one of the founding members of the Funk Brothers, the house band for MoTown Records. On many of the MoTown Records we heard, and still hear, on radio; Bob is the guitar player. But, as the e-mail informed me; Bob had died of cancer just a few years earlier. I am so happy he realized his musical dream.

MOTOWN’S FUNK BROTHERS (BOB ON GUITAR) AT A LOCAL APPEARANCE

Photo on the right shows (left to right) Robert White, Dan Turner, Earl Van Dyke, Uriel Jones, James Jamerson and local DJ Martha Jean Steinberg at Millie’s Chit Chat Lounge on 12th Street, Detroit.

LIFE ON OSAN AFB, KOREA

Our social life at Osan AFB would not have made much news in the social registers. Many of the young guys enjoyed going off base to the hootches, which others of us did not find appealing. The area was dirty, as you would expect to see in a country just coming out of a fierce war. The little bars and whatever the small village offered just were not that appealing. So, our social life was work, the Enlisted Men’s Club, and the rare USO shows that came over.

Because our exalted leaders chose to have the U.S. enlisted men share our club with the ROK Korean soldiers, we could never get on the pool tables or any other recreation. There were always 20 to 30 Korean soldiers lined up ahead of us to shoot pool or to do anything else. You might say the Enlisted Men’s Club should have been renamed the ROK Enlisted Men’s Club for the good it did us.

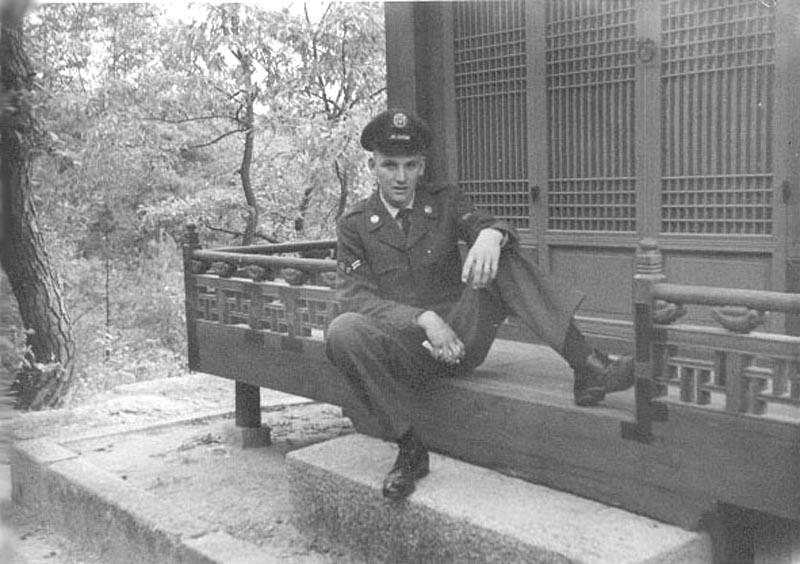

The USO took a group of us to Seoul on a tour. We visited the home of South Korean President Sigman Rhee. We were not allowed into the home; but did get to visit the surrounding area. From above we could view his home with his 16 car garage, most likely paid for by U.S. Foreign Aid money. Below is a photo of me taken at Sigman Rhee’s House of Meditation.

TDY TO FORMOSA (TAIWAN)

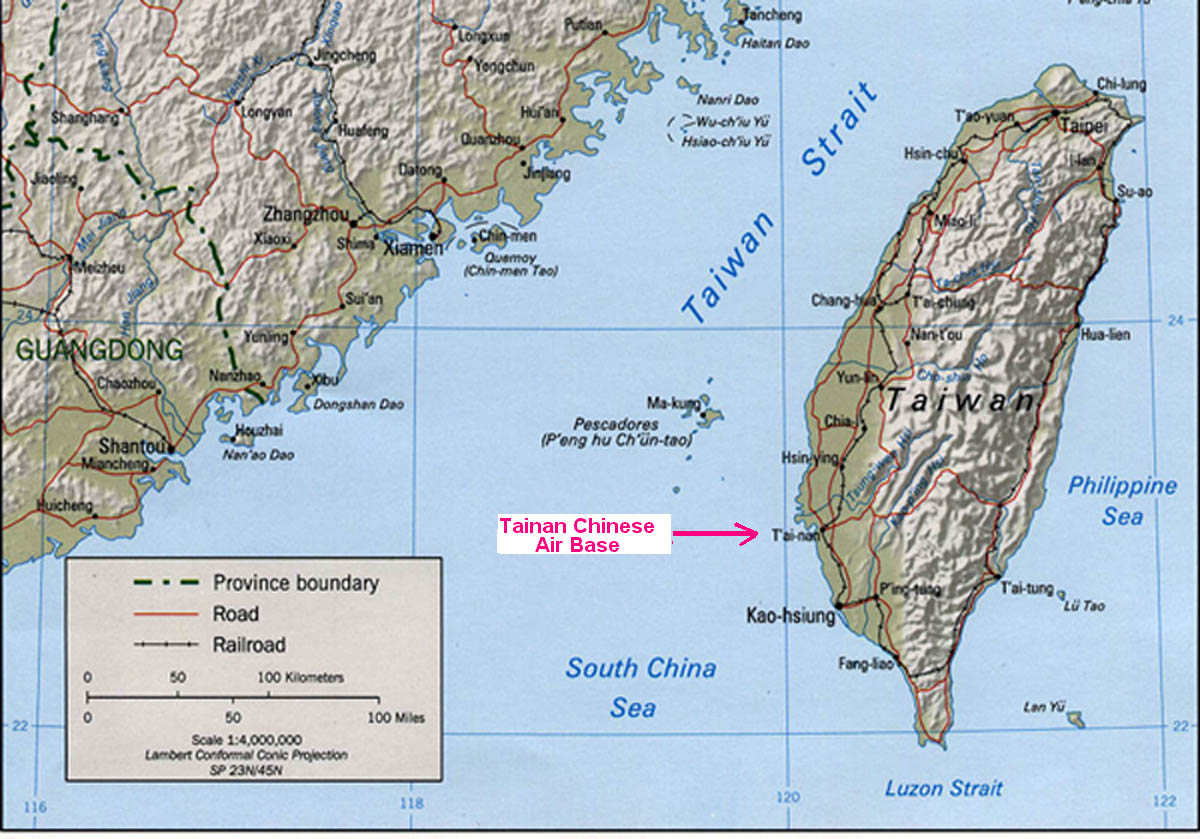

The three squadrons in the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing — 311th, 69th, 310th – rotated to Formosa for two month TDY tours. On the first of June 1956, the 311th packed up all our gear, loaded aboard C119 Flying Boxcar aircraft and moved to a Chinese Air Force base located at Tainan, Formosa (now called Taiwan).

The interesting aspect of our TDY tours to Formosa is that, at that time, our government called it a training exercise for us, to train us for quick deployment. Twenty-five years later, our government finally admitted that we were there as a determent to mainland China; to discourage them from attacking Formosa. And to support Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese military in case of an attack.

At this point, it might be good to take a closer look at why the three squadrons of the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing were keeping a constant presence in Formosa. In the late 1940s, the Nationalist Chinese Party, under the leadership of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, was being driven out of mainland China by the Communists. The last refuge for Chiang’s Nationalist Army was the island of Formosa.

Because Formosa had been under Japanese rule for fifty years, until liberated by the Allies during World War 2, the Formosans did not consider themselves to be Chinese. Actually, after fifty years, they were a mix of Chinese and Japanese; and considered themselves independent of China, and to be Formosans, not Chinese.

The Formosans did not want Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese coming to their little island. To them, this was an invasion by mainland Chinese. Chiang sent some of his leaders and troops to Formosa to prepare the island for their occupancy. By prepare, he meant to subdue any Formosan dissent. Although Chiang and his wife claimed to be Christians, possibly for U. S. political leverage, the way the Nationalist Chinese treated the Formosans was severe, as bad as any human rights charges the Western Nations have made against Communist China today.

By 1948, President Truman and his Democratic Administration were ready to write off Chiang and his Nationalist Chinese Party, who, by now, were near the point of being driven completely off the mainland of China to Formosa. Chiang knew his only chance to maintain leadership of his Nationalist Chinese Party and troops was to keep his promise of returning to the mainland a constant hope. Any hope he had of returning to the mainland was dependent upon the help of America; and now America was writing him off.

Two things kept Chiang Kai-shek alive politically. In 1950, Communist North Korea invaded South Korea and America became involved in the Korean Police Action. President Truman did not go to Congress to seek a declaration of war, but he had the power to send troops to aid an ally under the heading of a “police action.” With the onset of the Korean War (or Police Action), Formosa became an important Asian base for America, and we had to prop up Chiang once again.

During and after the Korean War, Chiang, knowing that Truman was not his champion, had to try to influence the next American presidential election. It is estimated that Chiang and his family had an accumulated $600 million to $1.6 billion war chest, mostly from American Foreign Aid. He spent a huge amount of this war chest on high priced public relations firms in America, in his attempt to influence the American presidential election. Did it work? Until then, the Democrats had been in the Oval Office for about 25 years. In 1952, General Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican, won the election and became our president. How much of this was due to Chiang Kai-shek’s publicity barrage we will never know.

We do know this. Chiang Kai-shek knew that the only way he was ever going to be able to return to power in mainland China was if he could get America totally involved in a war with Communist China and let America win it back for him. That was his goal; and much of his activity was aimed at getting America involved in a shooting war with China. That is why the 58th Fighter-Bomber Wing had a constant squadron stationed on a Chinese air base at Tainan, Formosa – and why there were several thousand MAAG (Military Advisory and Assistance Group) personnel throughout the island of Formosa.

When I look back on incidents which occurred while the 311th Fighter-Bomber Squadron was TDY on Formosa, I can now see Chiang’s hands in much mischief. The normal routine of a fighter-bomber squadron is to keep the pilots and ground crews sharp through simulated firing-bombing runs — and to improve their air-to-air firing accuracy, a flight of four planes would go up to fire at a long white target towed by another aircraft. Each of the four planes in the exercise were loaded with 50 caliber rounds with paint on the rounds. Each plane had a different color paint which adheres to the white tow target when it is hit. The pilot’s firing accuracy can be graded by the his number of hits.

Obviously, when a pilot is going up to fire at a tow target, he does not need bombs on his plane. However, when the Chinese pilots, flying American F-84s, went up to fire at a tow target, their planes also carried bombs. And, surprise, surprise – the tow target must have fired back, because the Chinese pilots frequently returned to base with holes in their fuselage. And all their bombs were gone – while shooting at a tow target.

One evening, during our second TDY tour on Formosa (December 1956 – January 1957) we heard on the radio news that Communist China had attacked Burma. None of us knew just where Burma was in relation to us sitting on Formosa; but we had an idea that things were about to heat up. The next morning, as we drove down the flight line going to work, we saw about a dozen bombers. I can’t remember now if they were B17s or B25s; but they were ferocious looking – with gun turrets on the top, on the bottom, at the rear, and in the nose of the aircraft. I am fairly sure they were B17 Flying Fortresses.

Needless to say, this made quite an impression on us; when, overnight, there were a dozen big bombers sitting all over the tarmac — on a fighter base. We were sure we were sitting in the middle of a war between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese Army and the Communist Chinese from the mainland. And being the bottom people on the totem pole, we GIs sitting on that Chinese air base on Formosa had to just wait and see. Possibly diplomacy prevented it; possibly a threat from the U.S. – but, I now know that, if Chiang Kai-shek had his way, there would have been a shooting war that day, with the U.S. right in the middle. Nothing would have made the Generalissimo happier.

Continued in Part 2